Jessie Marion King (1875—1949) was a Scottish designer and illustrator. She is perhaps best known for her work as a book illustrator, mostly of children’s books, but her many and varied skills included bookbinding, the decoration of ceramics and tiles, and book cover, wallpaper, textile and jewellery design. I love her jewellery designs so decided to write a short piece about her: her Wikipedia page focuses solely on her book illustrating career so I thought I’d try to fill the gap a little. If you want to know more about her book illustrations, here is a good starting point. But I am here for the jewels!

Jessie M King by James Craig Annan (autochrome, 1908).

Jessie enjoyed a successful career teaching and illustrating books and book covers, but as multi-talented and artistic people are often wont to do, she worked just as successfully in several other disciplines. From what I can gather, she first worked for Liberty in the very early 1900s designing wallpaper and fabrics, with commissions to design jewellery and silverwork for Liberty’s Cymric range following soon afterwards. She designed the jewellery but did not make it – that was undertaken by jewellers employed by Liberty.

Jessie’s jewellery designs can be broadly split into two types: pieces made with silver and enamel, often in quite large panels, only very occasionally with a freshwater pearl dangle, and generally more “Art Nouveauy” in feel:

Jessie M King design: silver and enamel pendant necklace and chain, dating from 1905. Made for Liberty & Co, its design is in the Liberty Pattern Book, model 8809. In the collections of the National Museums of Scotland.

Pendant necklace of silver, enamel and mother of pearl, designed by Jessie M King for Liberty & Co, 1904-1906. Collection of Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum, UK.

Silver and enamel buckle, designed by Jessie M King for Liberty & Co.

and those made with precious metals (often just gold, or gold with silver, or just silver), precious and semi-precious stones and/or pearls, and only small areas of enamel detailing, which are generally more “Arts and Craftsy” in feel:

Jessie M King design for Liberty & Co. Gold, moonstone and enamel brooch. Liberty model number 1800. Sold by Tadema Gallery.

Jessie M King design for Liberty & Co. Gold, silver, enamel and chrysoprase ring. Sold by Tadema Gallery.

Jessie M King enamel and blister pearl pendant. The drop is a later replacement. Sold by HomeFarmCottage on Etsy.

Jessie M King design for Liberty & Co. Gold, sapphire, moonstone and green enamel necklace. Sold by Van Den Bosch.

Jessie M King design for Liberty & Co. Gold, enamel and amethyst pendant. Liberty model number 8603. Sold by Tadema Gallery. Shows both of her common enamel motifs, the bud and the ‘lily of the valley’/three pointed flower.

Jessie M King for Liberty & Co. Silver, pearl and enamel pendant. Liberty model number 9257. Sold by Tadema Gallery.

Jessie M King moonstone and enamel necklace, for sale at Tennants Auctions.

Jessie M King design (attrib). Silver, citrine and enamel pendant. For sale at VictoriaSterling at Etsy (click on photo for details).

Jessie M King design for Liberty & Co. Moonstone, enamel and silver pendant. Sold at Tadema Gallery.

Jessie M King design for Liberty & Co. A Glasgow School gold and sapphire necklace, Liberty Pattern Book model 8498. Sold by Van Den Bosch.

Her colour palette is overwhelmingly blue, green and purple. I have to add this is my personal take on her jewellery and I am no expert!

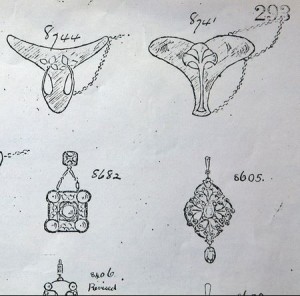

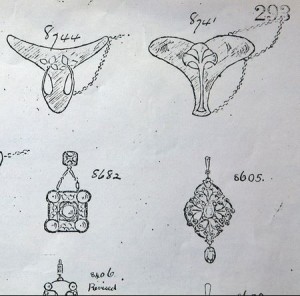

The Liberty Pattern Book holds many of her original designs, each one numbered.

Some of Jessie M King’s jewellery designs in the Liberty Pattern Book, with model number. Pattern 8605 (bottom right of the drawings) is shown in its realised form below.

Jessie M King design for Liberty & Co. Gold, amethyst and enamel pendant. Liberty Pattern Book model 8605, shown above.

UPDATE 10 November 2015: Last Sunday’s Antiques Roadshow featured a necklace that I am 100% certain was designed by Jessie, although it was not identified as such. I grabbed a few screenshots and wrote a blog post on the necklace, with illustrations of other, similar design by Jessie.

A brief biography:

Jessie was born in New Kilpatrick, near Bearsden in Dunbartonshire, and studied at the Glasgow School of Art from 1892. Here she was influenced by, and later herself influenced the world famous Glasgow Style, a development of Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements. While at the School she was a member of what was later known as the “Glasgow Girls” group of female artists, and met and formed lifelong friendships with artists such as Helen Paxton Brown and Mary Thew.

Jessie was an award-winning student, and in 1899, the same year that she graduated, she was appointed Tutor in Book Decoration and Design at the School of Art, where she continued to teach until 1908. Her first commissions were for book covers, with book illustrations following in 1902, and it was around 1904 that she started to design fabrics for the famous firm of Liberty & Co. of London and just a little later jewellery, also for Liberty.

She embarked on a study tour of Italy and Germany in 1902, and the next year became a committee member of the Glasgow Society of Artists. In 1905 she joined the Glasgow Society of Lady Artists. Her first solo exhibitions were at the Bruton Street Gallery in London in 1905 and at the studio of T and R Annan (Annan’s Gallery) in Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow, in 1907.

Glasgow School of Art, designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Photo by Ad Meskens.

After a ten year engagement, in September 1909 Jessie married the artist E A (Ernest Archibald) Taylor, and moved with him to Salford where he worked designing for the firm of George Wragge Ltd. Here their only child, Merle Elspeth, was born. The family moved to Paris in 1910, again for Ernest’s career as he had gained a teaching position at Ernest Percyval Tudor-Hart’s studios. In 1911 Jessie and Ernest set up their own art teaching school, the Shealing Atelier. While in Paris Jessie met and was influenced by artists including Henri Matisse, Marie Laurencin, Théophile Steinlen, John Duncan Fergusson, and Samuel Peploe; she also learned the art of batik. The couple ran summer schools on the Isle of Arran in Scotland.

The progress of World War I meant that Jessie and her family had to return to Scotland in 1915, and they settled in Kirkcudbright, at Greengate, a house on the High Street Jessie had bought in 1907 before she was married, and where she was to live for the rest of her life.

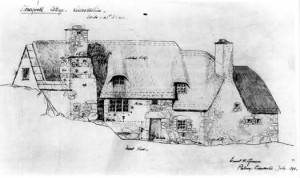

Jessie M King and E A Taylor’s house, Greengate, in Kirkcudbright. The entrance to the ‘Greengate Close’ is through the open gate on the right.

Jessie and Ernest gathered artists around them, and an artists’ colony known as the “Greengate Close Coterie” became established in the cottages along an alley behind their home. Friends and visiting artists would stay, sometimes for extended periods, and “according to Robert Burns, of Edinburgh College of Art, no student’s training was complete without a stay in one of the cottages at their home, Greengate.” The cottages in the Close were known by the colour of their front doors.

Jessie was an eccentric character. She dressed flamboyantly, with a fondness for wide-brimmed hats and buckled shoes, long after these had gone out of fashion. One woman, recalling her childhood in Kirkcudbright, remembered Jessie “riding through the streets on her bicycle … We all thought she was a witch!”. Jessie believed that she had second sight, and had been strongly influenced by Mary McNab (d. 1938), her devoted Gaelic-speaking nursemaid and later housekeeper who possessed a wealth of folk tales. Jessie was so connected with Mary that her ashes were scattered on Mary’s grave.

By the way, if you want a Greengate Close Coterie holiday, the house in which Jessie and Ernest lived in Kirkcudbright is now a B&B.

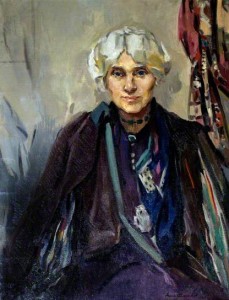

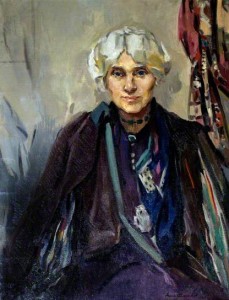

Portraits of Jessie:

Jessie M King.

Jessie M King.

Jessie M King painted by her husband E A Taylor. Undated.

Jessie M King.

Jessie M King by James Craig Annan.

Jessie M King by Ernest Archibald Taylor.

Portrait of Jessie M King by Helen Paxton Brown, undated. In the collections of the National Portrait Gallery of Scotland.

Portrait of Jessie M King by Helen Paxton Brown, undated. In the collections of the National Portrait Gallery of Scotland.

Jessie M King by Lena Alexander. (c) Dumfries and Galloway Council (Kirkcudbright); Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

Jessie M King.

Sources: Jewelry and Metalwork in the Arts and Crafts Tradition by Elyse Zorn Karlin, 1993, 139-140; Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry for Jessie Marion King by Jan Marsh; Jessie M King entry in the ExploreArt at Gracefield Arts Centre website; Jessie Marion King entry in Artists in Britain Since 1945—Chapter K by the Goldmark Gallery; the Jessie Marion King Papers at the University of Glasgow; Jessie Marion King entry in In the Artists’ Footsteps; Jessie M King page on Wikipedia.

This great blog has lots of photographs of Jessie’s illustrations, book covers, painted pottery and other artworks.

Further reading: The Enchanted World of Jessie M King by Colin White, Canongate Publishing Limited, 1989; Jessie M. King and E. A. Taylor: Illustrator and Designer. Sotheby’s Sale of 21 June 1977 at the Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society. Glasgow: Sotheby’s Begravia, 1977. No. 169; Glasgow Style by Gerald and Celia Larner, Paul Harris Publishing, Edinburgh, 1979; Glasgow Girls: Women in Art and Design 1880—1920 edited by Jude Burkhauser, Canongate, Edinburgh, 1990; Tales of the Kirkcudbright Artists by Haig Gordon, Galloway Publishing, Kirkcudbright, 2006; Glasgow Girls: Artists and Designers 1890—1930 by Liz Arthur, Kirkcudbright, 2010.