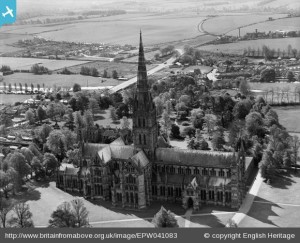

My heart is in the past, and that is why I love this website: Britain From Above. In 2007 English Heritage, the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS), and the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (RCAHMW) acquired the historic oblique aerial photography archive of Aerofilms, a company set up in 1919 for commercial photography from the air. Usually the photos were taken for clients, maybe to establish the location of a building plot within the landscape, or to show the progress of a large construction site or the condition of a property, or as views to be sold to postcard manufacturers, but they have other significances too: the most important part of the collection spans the years from 1919—1953, and document a now-lost England, Wales and Scotland (sadly Northern Ireland is not part of the project). Currently there are over 96,000 digitised images in the collection.

I can—and do—lose hours on the Aerofilms website. If you register as a member (it’s very easy to do so, and free), you are able to zoom in on the photographs. The negatives have been scanned at such a high resolution that the tiniest details become clearly visible. They show snapshots of a long-lost Britain: stooks of wheat in a field after harvest; horse-drawn ploughs; airmeets for the dashing 1920s and 1930s aviators where planes are simply landed in a suitable flat field; steam engines puffing along pre-Beecham railway lines; film sets from the 1930s; even the R-101 on its first test flight. You can search by date, by co-ordinate, or by placename.

The project encourages users to contribute information on places by tagging the images or adding data, photos, videos or links in a free text area. There are galleries which include all the images taken on a single flight, and even a gallery for so-far unidentified images, where the information accompanying them is lost or incorrect, and members have helped successfully re-attribute many of the photos in the collection. Some of the photos are on glass plate negatives which have been damaged—yet another reminder of a lost time.

Many of the photos are of cities and built-up areas, but as my heart is in the countryside as well as in the past, I tend to stick to looking at the photos of rural areas.

I have used Britain From Above for my archaeological research work: sometimes I undertake projects where I have to find out as much as I can about a particular area or site, and how it has developed over time. For this I will use documentary sources (books and articles, plus written documents such as letters, wills, diaries, estate accounts etc), maps and plans, drawings, paintings and sketches, and where available, photographs. The Aerofilm vertical photos at 1:10,000 scale are an amazing resource for identifying landscape features such as earthworks, and the oblique photos on Britain From Above are also very useful as they are often taken from a much lower altitude and so have much more detail. Earlier this year I worked on a project for the history of a house and plot near to Hampton Court Palace in Richmond upon Thames, London: the Aerofilm photos provided great details about its development from the 1920s onwards.

Britain From Above is a fantastic resource (especially for schools) and a complete time-sink. Once I log on, that’s it for a couple of hours …