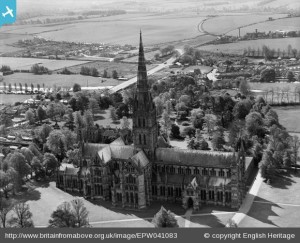

It was a chilly and blustery day today, and we went on a lunchtime walk up on Cold Kitchen Hill, which rises above the Deverills in southern Wiltshire. The Deverills are a set of villages in the Deverill River valley which wends its way between between chalk downs, and there are five of them: Longbridge Deverill, Hill Deverill, Brixton Deverill, Monkton Deverill, and Kingston Deverill. We parked by Kingston Deverill Church, where we saw our first flowering snowdrops of the season in the churchyard.

Scattered snowdrops in the strangely headstone-free churchyard of Kingston Deverill church.

Spring is definitely on its way—the birds are twittering and the buds are fattening. The cow parsley is starting to grow—it always strikes me how early in the season it gets going, but then again it has to be at full height and flowering by late April, so that’s not such a surprise really, I suppose. A raven cronked overhead as we walked away from the church.

As we walked along the road two racehorses were being unloaded from a horsebox and were ridden off. We followed the road to one of the many footpaths and bridleways that cross the hill, meeting the racehorses and their riders. Later, as we climbed the grassy slope, we could see them being ridden at a fair lick over the hill in the distance.

Looking south from the lower slopes of Cold Kitchen Hill, towards Kingston Deverill.

From the same spot, looking eastwards up the valley towards Monkton Deverill.

A lovely flock of fieldfare, maybe fifty or so, flew over us, and reminded us of our lone visitor (he was still there this morning patrolling the lost garden—I check every day to see if he is still with us). We met a lady, flushed of face and runny of nose, with two serious looking walking sticks, and we stopped and had a natter. She hadn’t seen the fieldfare or the raven but introduced us to a wonderful new term—crookdaws—for flocks of indeterminate black corvids/mixtures of crows, rooks and jackdaws.

Lovely chalk downland from Cold Kitchen Hill.

Then onwards and upwards. We startled a hare and it hared off, making a wide circle around us. We wandered over to the trig point on the summit (a mighty 257 metres above sea level). The trig points are built on high points around the country by the Ordnance Survey, the veritable surveying and mapping agency for the UK. The trig point (or trigonometry point, to give it its proper name) is a concrete obelisk with a flat upper surface, into which are set the fittings to accommodate the base of a theodolite.

The top of the trig point, showing attachment fittings for a theodolite. In the blurry middle distance is the beacon, a metal basket atop a high pole.

On the site of the trig point is a bench mark, the height of the top of the horizontal line of which is established in metres above sea level (m ASL). They are invaluable not only for map makers, but for archaeologists and architects and builders and surveyors—in fact, anyone who needs to know the absolute height of where they are. In our archaeologising days Chap and I frequently had to go hunting for bench marks. Their location is marked on OS 1:2,500 maps, along with their value in m ASL, and they are usually on buildings like churches or other structures that are assumed likely always to be there, and unlikely to be demolished.

The bench mark on the trig point on Cold Kitchen Hill.

Anyhow, one of the basic features of a bench mark that it has to be level and unlikely to move, as of course this will alter its height and thus make any readings taken from it inaccurate. So we were somewhat amused by the appearance of the one on Cold Kitchen Hill. The ground at one side has been poached out into a hollow, presumably by cattle or sheep trampling there and resting against it, and so the whole thing leans at a drunken angle, making both the theodolite base and the bench mark, both of which need to be level to be of any use, rather useless.

Chap and the drunken trig point on Cold Kitchen Hill.

In the distance we could see the beacon which had held the ceremonial bonfires that were last lit across the country in 2012 to celebrate the queen’s diamond jubilee, a rekindled (sorry, couldn’t help it) tradition that harks back to the days when the fastest method of transport was by horse, and so lighting fires in beacons on prominent hills was a far quicker way of relaying a message. Beacon Hill is a very common hill name in the UK, for just this reason. Beyond that, on the horizon, is Alfred’s Tower, a fantastic folly near Stourhead. In another direction we could see Duncliffe Hill and the escarpment on which Shaftesbury sits. And to the north-east was Salisbury Plain. Gliders were flying from the nearby Bath, Wilts and North Dorset Gliding Club.

Beautiful skyscape, looking NNE from Cold Kitchen Hill towards Warminster.

It was very windy and pretty cold—the kind of keen wind that makes your mandibles/ears ache, for some reason, so we headed back down the hill. We scared a lark from its roost in the grass, but it settled nearby very quickly. On the way we noticed an abandoned ranging rod in the fenceline by the Mid Wilts Way, the sort we have used many times on archaeological sites, for surveying and to serve as 2 metre scales in photographs. I assume it was left by a surveyor, possibly an archaeologist, and forgotten. It was a wooden one, which dates it—most are metal and come in two parts these days.

The abandoned ranging rod. Note the bottom hinge on the gate made of the farmer’s best friend, baler twine.

When we got back to the car we decided to have a look around the church—but that’s for another post, I think.