Chap came back from a Sunday trundle in his Land Rover up on to Salisbury Plain with a bag full of sloes. We make sloe gin and sloe vodka most years. We also make damson gin and vodka, and greengage gin and vodka when we can get hold of those rare little green beauties. Sloe gin is a wonderfully warming winter liqueur, and it also makes a great base for a kir royale-type drink, made with cava (or champagne if your pockets are a bit deeper).

There are various schools of thought about when is the best time to pick sloes. Some say they should only be picked after the first frost; others bypass this by sticking them in the freezer overnight; others (like us) don’t bother and pick them when they are ripe, frost or no frost, and no freezer malarkey. I can honestly say I cannot tell the difference between any of these methods in the resulting drink they produce, but maybe I’m just a lush with a very unsophisticated palate.

The sloes seem to be getting riper earlier with each passing year: in 2011 we picked them on 3 October: this year it was on 31 August.

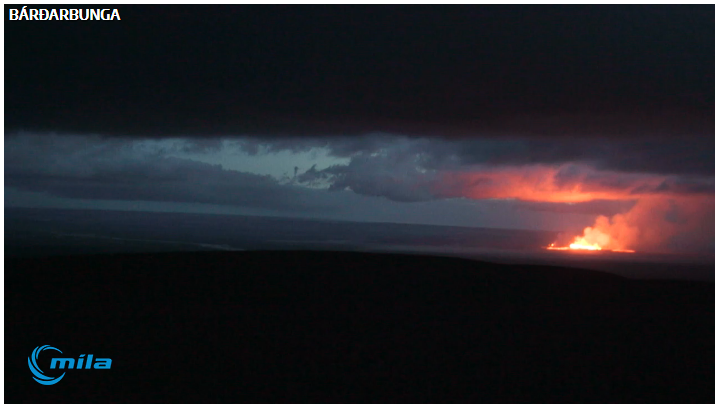

Last year’s batch waiting to be strained and bottled up. Left to right: sloe vodka, sloe gin, damson vodka, damson gin.

And as for the recipe itself, it couldn’t be any easier.

Sloe gin (or vodka)

(Can be made with any soft or stone fruit, really—damsons, greengages, mulberries, blackberries, raspberries, strawberries …)

Wash the sloes and drain dry. Pick out any leaves or stems. Prick each sloe (I do this with a fork, holding two sloes at a time). This allows the juices to get into the gin (or vodka) more easily. Fill a 1 litre bottle to halfway up with the sloes (you’ll need a wide-mouthed bottle if you are using damsons or greengages). Add 2 tablespoons of caster sugar. Top up with gin (or vodka).

Leave in a dark place for at least 6 months, gently agitating the bottle every few weeks (if you remember—I sometimes forget and it doesn’t seem to matter much). Strain off the sloes through a muslin-lined colander. It’s best to leave the sloes sitting in the strainer for a few hours to allow the precious liqueur to slowly drip out. Bottle up the sloe gin (or vodka) into a clean, sterilised bottle.

Don’t throw the sloes away. They are too small and bitter to make into a pie filling (as we do with the damsons and greengages); instead, put them back into the bottle and top up with dry white wine and leave for a couple of weeks. We get several bottles of wines-worth from the sloes before they stop giving up their boozy, sloey flavour into the wine.

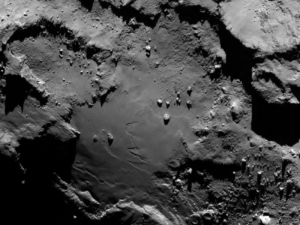

Sloe vodka made yesterday (3 September 2014) on the left, sloe gin made on 1 September on the right. I haven’t shaken the vodka and you can see about 1cm of colour hovering above the sloes.

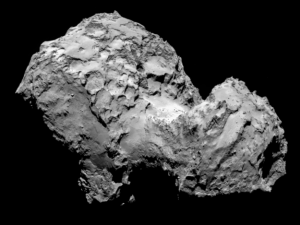

One shake later: hey presto! Need to buy a bit more vodka to top the bottle up, and then it’s into the back of the cupboard with them.

We normally bottle up the previous year’s sloe gin and vodka about the time we are making beech leaf noyau (another lovely liqueur that we make in early May), so they have about 8 months’ steeping; this year we forgot and so the sloes have been steeping 3 weeks short of a whole year. Some people reckon their sloe gin is ready by Christmas, but we’ve tried it then and the flavour hasn’t fully developed in four months. It’s definitely worth the wait!