Chap and I headed out to Stourhead this morning to get a fix of autumn colours. The gardens open at 9 and we got there at about 9.30, and there were already plenty of people there. Unsurprisingly most of them seemed to be taking photos.

We did our usual circuit walk around the lake, anticlockwise this time. The colours are pretty good this year but I wonder if the best is still to come.

The Pantheon, newly reopened after restoration works this summer. Look at the red of that acer – it gives that lady’s coat a run for its money!

Looking back at the river god through the grotto. Love the pebble floor! To the right in this view is the sleeping nymph.

On the drive home from Stourhead, just to the south of the gardens en route to the wonderfully named village of Gasper: a fantastic little estate smallholding, with outbuildings for livestock. We could see geese, ducks and guinea fowl!

The autumn colours are still developing. Alan Power, the Head Gardener at Stourhead, gives updates on his Twitter feed, as well as tweeting some amazing photos (he’s definitely got a better camera and waaaaaay more skill than me!).

On it I found out that in August this year the gardens at Stourhead were Google mapped: soon you’ll be able to take a virtual walk around the estate, courtesy of Google and this young man!

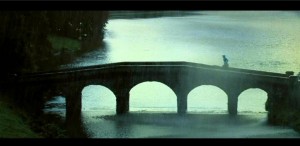

And I have to include this photo that I found on Alan’s twitter feed: it’s the most stunning view of Stourhead, taken by James Aldred in May this year from one of the taller trees on the estate:

Stourhead. Stunning photo by James Aldred in May 2014, showing the Temple of Apollo on its heights, and the Palladian bridge in the foreground.

Update on Friday 31 October: I have just heard Alan Power on BBC Radio 4’s PM programme, doing his annual description of the gardens, interviewed by the wonderful Eddie Mair. Alan has such a poetic way of describing the gardens, and his horticultural contributions are rightly a favourite part of PM’s annual cycle. He was recorded this afternoon, chatting for about 8 minutes on the programme, with the full 11½ minute interview available here. It’s well worth a listen: he clearly adores his job, the gardens, the plants and the people who visit, gaining pleasure from their pleasure, and he has a great eye for detail and a passion to share his delight in these fabulous gardens. A few lyrical snippets:

‘Trees in full autumnal song’

‘Early last week we had some wind come through the country … and on its way it undressed some of the trees’

‘On the island there’s a tulip tree that’s been rattled by the wind a little bit and its internal branches have no leaves left and it’s just haloed with a golden yellow’

‘And there’s architecture in the plants as well … looking across to the trees in the distance and there are some poplar trees and some birch trees by the grotto at Stourhead and they’re, they’re bolt upright you could describe them as, so their stems are really striking from a distance, really grey stems and they’re almost the same colour as the columns on top of the Pantheon, so you’ve got architecture within the soft planting and you’ve got the harder architecture of the eighteenth-century temples.’

‘The leaves have been falling gently and they haven’t been frightened by the frosts.’

Alan has been talking to PM about the autumn colours at Stourhead for six years now, and it’s just a delight.